Loved abroad, savaged in Norway.

This is a very concise and to-the-point summation of the reception Marianne Heske and her work received in 1980 when she took a 350-year-old hay barn from a mountainside in Sunnmøre and turned it into a work of art.

“The hay barn was used to store hay for goats when they were put out to grass in the mountains. It wasn’t something that anyone would consider being worth very much at all. Heske challenged that view by putting a spotlight on it and placing it in The Centre Pompidou in Paris,” says Karl Olav Segrov Mortensen, who is a curator at Kunstsilo and is currently working on a doctoral project on Gjerdeløa at the University of Agder.

He explains that even though the hay barn is the main focal point of the project, the processes behind it are what make it a work of art. That is why the term ‘conceptual art’ is used in connection with it, and it is often attached to Heske’s work.

“She uses the occasion to engage different processes and thus create a larger work. The public has a role and the people who moved the hay barn have a role, and Heske documented everything that was going on. Consequently, she set in motion an art historical narrative that pushed some boundaries as well as challenging some conservative perceptions that were current at that time about how to think about art,” explains Mortensen.

Transported in a van

The project started with Marianne Heske’s selection as one of three artists that would represent Norway at the important Biennale de Paris exhibition in 1980.

“I chose this project because the hay barn has a long history. It is 300 years old. Think about everything that has happened to it there, and in that surrounding nature. You won’t find anything that stands in greater contrast to Paris and the Pompidou Centre’s architecture than this,” said Heske.

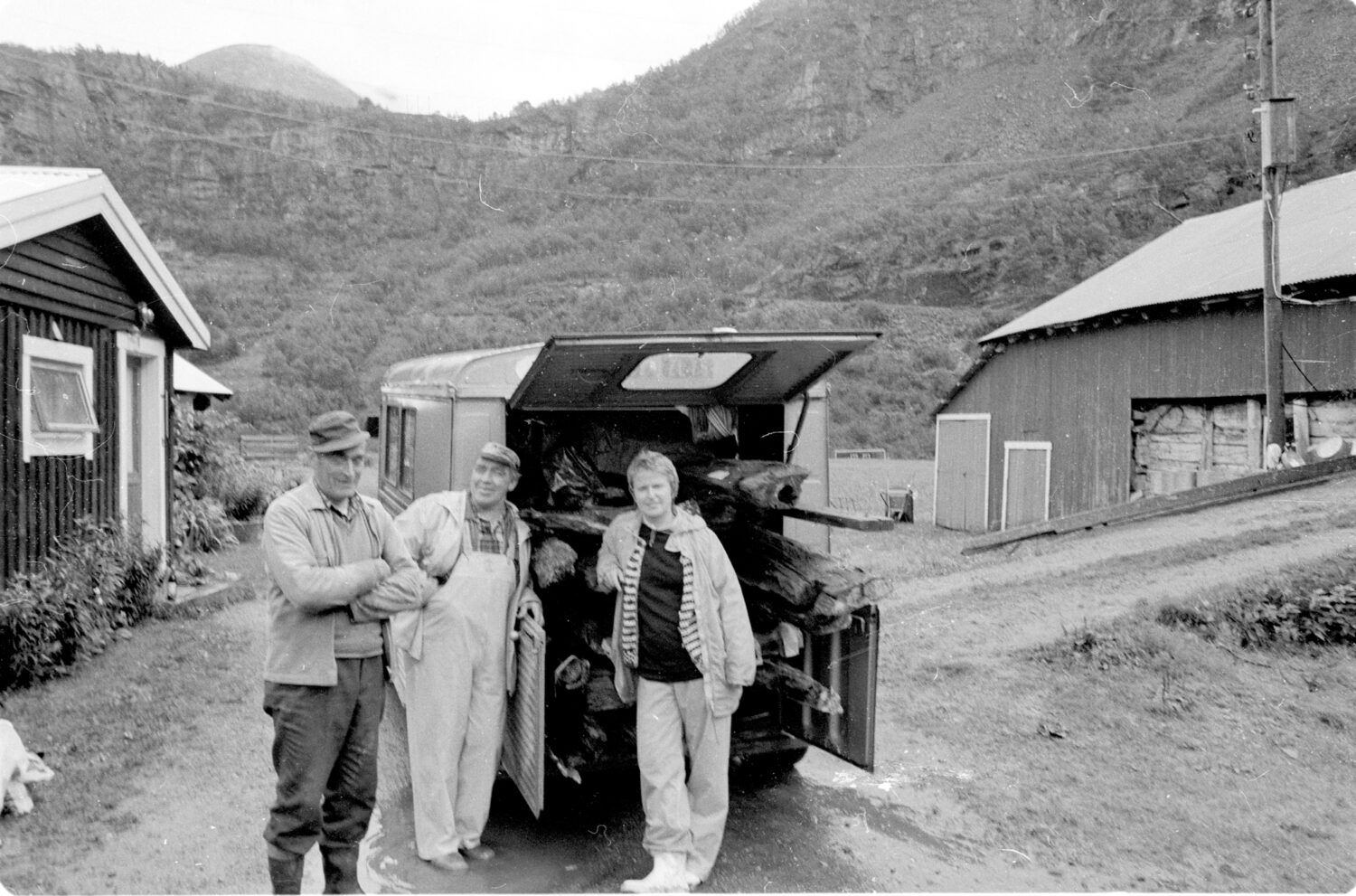

The artist was allowed to borrow the hay barn from the owner for one year. She dismantled it, took it down from the mountainside with the help of some locals, put it in a van and transported it to Paris.

“It was installed in The Centre Pompidou, which at the time was a three-year-old, ultra-modern art museum. Two rooms were built for the project, one for the hay barn and one for the photographs documenting the processes. In addition, she showed two videos. One of them was of the hay barn in its natural element on the mountainside in Tafjord, while the other one showed the public as they examined it in the museum. The contrast between the two is the first thing the visitors met,” says Mortensen.

Heske says that the guards watered the roof of the building, so that the heather on top would continue to grow.

“One of them cursed and swore at me because he said he wasn’t being paid to water art, but only to water plants,” she chuckles.

There are inscriptions on the walls of the hay barn by people who have been to it throughout the years, going all the way back to the 1680s. In Paris the public was also invited to carve their name or initials inside.

A different culture

The Biennale in Paris received significant coverage in the international press, and Gjerdeløa was singled out by many reviewers and journalists.

“They thought it gave a window to a different culture that people were not used to coming across in the metropolis of Paris, and that it said something about how people manage to live in harmony with nature. There were many who also found it exciting and interesting that she moved an existing object, as well as showing the process behind it, instead of making something completely new,” says Mortensen.

A team of six people had helped Heske move the hay barn. Photographs documented this as well.

“A sequence of photos was taken which show how the team of volunteers moved all of the parts of the hay barn down the mountain. They could have done it with a helicopter, but Heske insisted that it be done with cables in order to emphasise the old-fashioned methods used for doing such a thing,” says Mortensen.

Conservative reception in Norway

After having been seen by 140,000 people at the Biennale, the hay barn was moved back to Norway and then installed at the Henie Onstad Kunstsenter at Høvikodden in Bærum. After receiving positive coverage in the French capital, the reception in Norway was something else.

“It’s as if the people who are not educated in art, people who are relaxed and unaffected, understand conceptual art better than the scholars do. That was the case with Gjerdeløa. It was viciously torn apart in the newspaper Aftenposten with some rather scathing articles. For people who have an education in art history, and sort of have some expertise, my work doesn’t really click with them,” says Heske.

She says that when she applied for a work grant after doing Project Gjerdeløa, someone on the jury suggested that she rather could get one from the Ministry of Agriculture.

“That’s how it was, and you got used to it. What was considered to be art elsewhere in the world was looked upon in Norway as something connected to the life of peasants,” Heske says.

Mortensen explains that while the art community was conservative in Norway, art was viewed more open-mindedly in Europe. The reactions to Gjerdeløa reflected this.

“Heske has also contributed to highlighting these contradictions along the way. All contrasts are an important part of the project,” he says.

In recent years Gjerdeløa has been pointed to by art historians as one of the central works in Norwegian art. In 2005 the newspaper Morgenbladet named it as one of Norway’s most important works in the post-World War II era.

Into Kunstsilo

After being displayed at the Henie Onstad Kunstsenter, the hay barn was returned to its original site in Tafjord. It stood there for 30 years before it was exhibited once again at the Astrup Fearnly Museum of Modern Art in 2014. At that time Heske expanded the project by making a replica of the hay barn in synthetic resin. It was placed next to the old, authentic hay barn, so that the two of them could appear as each other’s opposite.

In 2019 Project Gerjeløa was purchased for the Tangen Collection. According to plan the hay barn will be in its own separate area in Kunstsilo at the top of the silo.

The Tangen Collection already has 21 works by Marianne Heske. Her art has also been purchased by, among others, the National Gallery and the Norwegian Riksgalleriet in addition to a large number of public and private collections in different countries. Within the context of Norway, Heske has undoubtedly contributed to moving the art community forward.

“Everything I do revolves around moving the human mind so that it doesn’t get stuck,” she says. “That’s a part of art’s task. When people sit inside their boxes, they don’t go anywhere. Art can challenge our fixed attitudes. As far as I’m concerned, my work is primarily about opening people’s minds.”