We are in the middle of the harsh thirties. It has been six years since the start of the stock market crash in the USA, also known as Black Tuesday. Just a few weeks ago the Norwegian government had to resign following a sharp increase in unemployment. There are 2.8 million people living in Norway, 18,000 of them in Kristiansand.

These are tough times, but in Kristiansand, “the capital of Sørlandet,” things are happening; something that arouses interest and curiosity, and hope for some new jobs.

It all takes place on the island of Odderøya. A bathing spot and an industrial area will now become the location for one of Sørlandet's premier landmark buildings. A grain silo, which will eventually become an iconic building for Kristiansand. And a subject of much debate in the region.

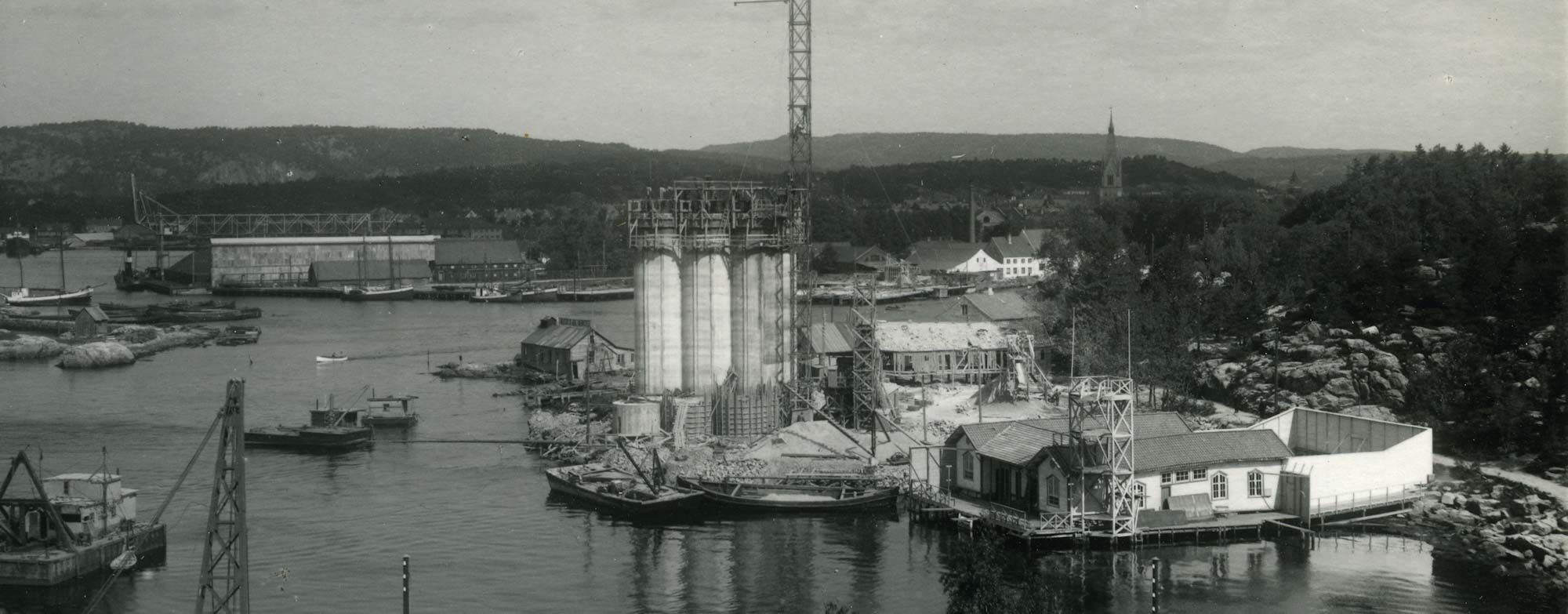

On April 8, 1935, a few weeks behind schedule, the casting work on Odderøya begins.

Emergency Storage

“Three things made the timing for the silo perfect,” says historian and former director at Vest-Agder County Museum, Jan Henrik Munksgaard.

“Kristiansand needed a deep-water quay. The America boat had to sail into the middle of the harbour, and passengers would then be transported to the pier in small boats. It was far from ideal. At the same time, Statens kornforretning (‘The national state grain enterprise’) had obtained a monopoly on grain import, and wanted an emergency storage in Kristiansand, as they had elsewhere in the country. In addition, Christianssand’s Mills decided they needed a new place to store their grain. All these things happened around the same time, and it worked out well,” says Munksgaard.

In 1933, the manager Arthur Fr. Eriksen at Christianssand’s Mills contacted the architectural firm Korsmo og Aasland in Oslo, to inquire if they could consider designing a new silo for the company. The response was positive.

It was no coincidence that manager Eriksen at the Mill contacted Arne Korsmo, an excellent young architect who had gathered influences from functionalism on a study trip across Europe in the late 1920s.

“In the 1930s, Korsmo designed several buildings that are among the main works in Norwegian functionalism. The background for his idea on Odderøya was American grain silos. They were constructed of reinforced concrete, and their appearance was insignificant. Only their function mattered,” says Munksgaard.

Sketches and drawings were presented in 1934, and well received. The Mill secured a plot on the new deep-water quay, and everything was set.

Local Workers

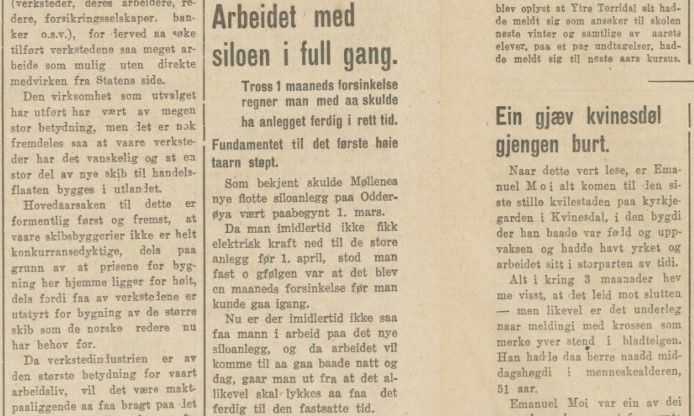

According to the local newspaper Fædrelandsvennen in 1935, there were problems with the power supply that delayed the construction by a few weeks. When work began at the beginning of April, the Oslo company Høyer Ellefsen was tasked with executing the project. Exactly how many workers were involved is uncertain, but Fædrelandsvennen reported that there were ‘quite a few.’

“Ellefsen used local labour, and most of the workers were from Kristiansand. And this was momentous in the area. Such a large and special building meant something for the city. And historically, it has been one of the most interesting buildings in Kristiansand. An icon for the city's architecture,” says Munksgaard.

Photo: Statsarkivet / Agderbilder.no

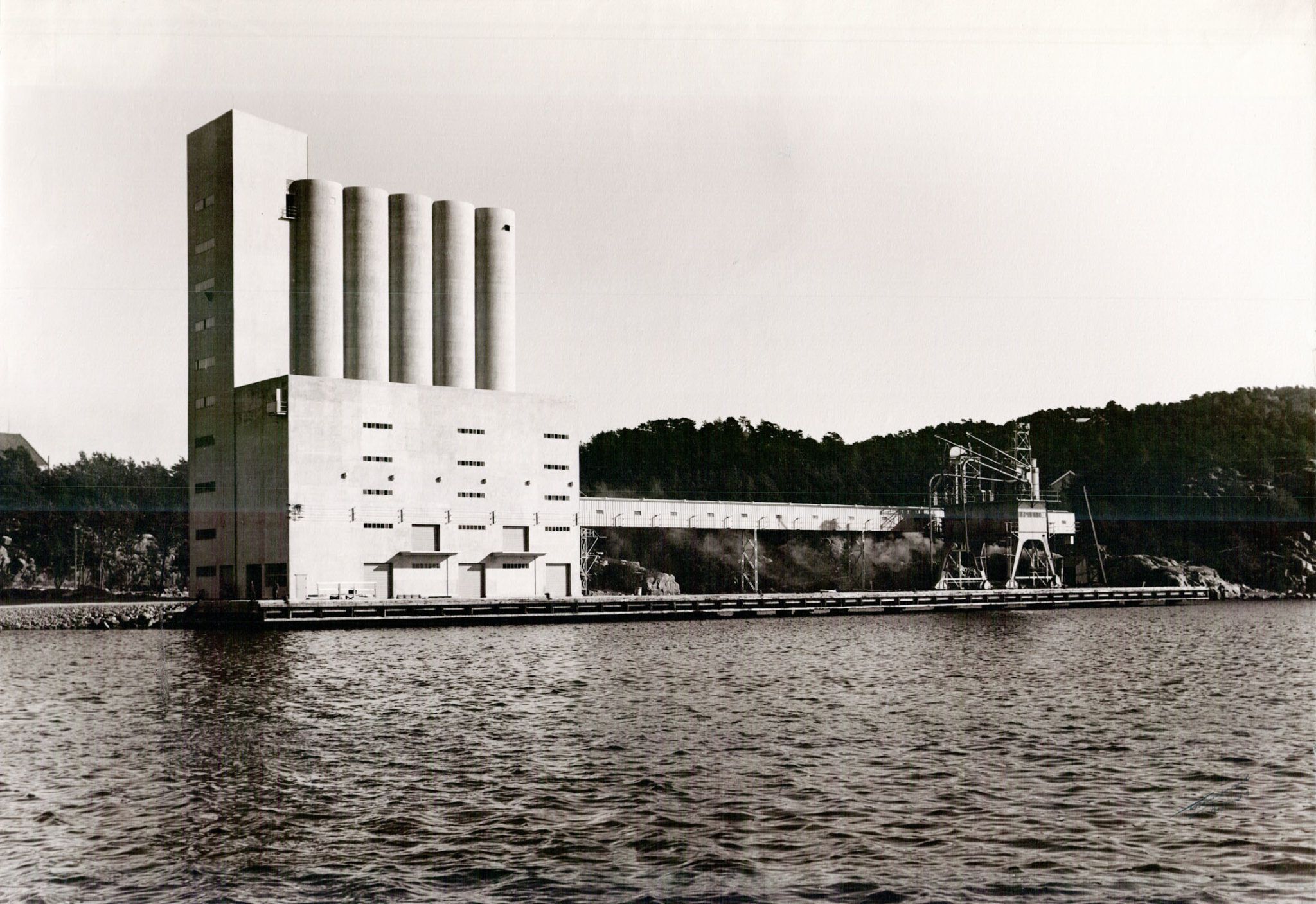

The building was the first to represent functionalism in Kristiansand. The style is distinguished by its minimalist aesthetic, featuring expansive surfaces, clean straight lines, and distinct geometric shapes. This architectural approach gained prominence in the 1920s and made its way to Norway by the 1930s. Following its arrival, functionalism became the prevailing architectural trend throughout that decade.

“The silo was meant for storage, emptying, and storing of grain. It could not be more functional. In Kristiansand, the silo is the most typical functionalist building we have had,” says the historian.

The silo housed 15,000 tons of grain

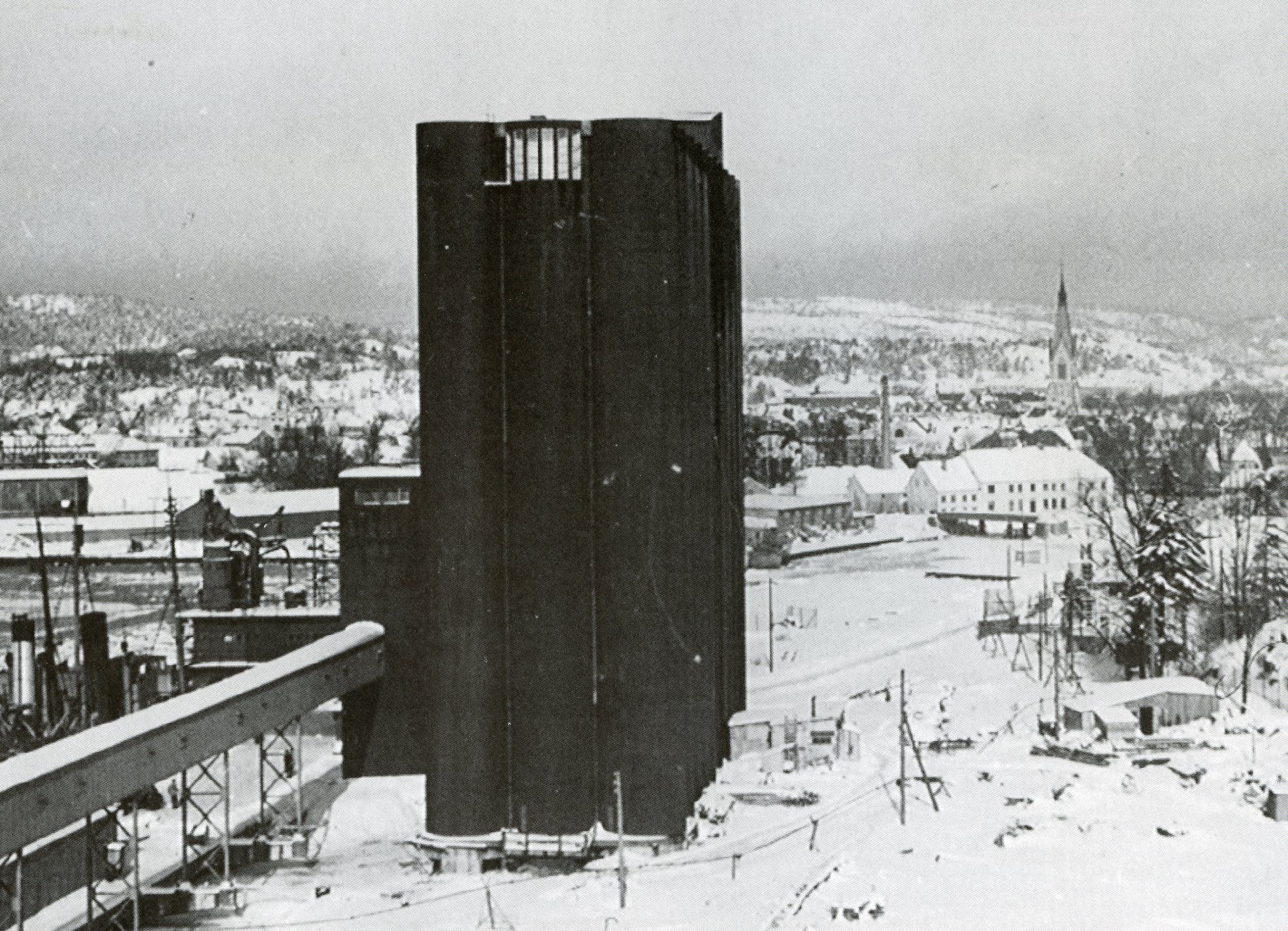

The grain silo was the first building in Norway to be erected using the slip formwork technique. This involved moving the formwork upwards before the concrete was dry. This allowed for quick and economical construction, and the structure was strong because there were no joints in the concrete. In later times, oil drilling platforms have been erected using the same principle.

The grain silo at Vippetangen in Oslo, which was completed two months earlier, was the first functionalist silo in the country, and the silo in Kristiansand was the second. Since then, many more have followed.

The silo on Odderøya consisted of cylindrical cells, an elevator tower, and a storage building. The fifteen cells, thirty-eight meters high, were erected in a rhythmic, undulating form. These were built over three weeks in the summer.

The silo could hold up to 15,000 tons of grain and was put into use in December 1935.

In 1939, the structure was expanded with the addition of fifteen new cells. That same year, the architects Kosmo and Aasland received the prestigious Houen Foundation Award for the grain silo on Odderøya.

Shutdown

There was a large wheat production in the 1930s, but the grain in Norway was of inferior quality. As a result, the primary sources of grain imports were the USA, Canada, Argentina, and Russia. The grain was loaded into the silo from a supply channel in the new harbour and blown into the cells.

Photo: Privat

The employment opportunities at the silo were few, but permanent. For those who got a job, it was a safe and predictable career.

“The Mill had workers down at the silo, and grain was transported daily to the Mill. It served as a continuous lifeline connecting the two locations,” says Munksgaard.

The grain silo was an immense success, and Christiandssand’s Mills did well. Norwegian mills operated with high efficiency, producing a surplus beyond the population's needs. The decline in this industry was primarily due to societal shifts towards greater urbanization.

“The Mill in Kristiansand was the smallest of the trade mills in Norway, and when the grocery stores and bakeries began to centralize in the 1980s, there was no need for so many mills anymore. Then Christianssand’s Mills was bought out and it did not take many years before they wanted to shut it down. Not because it was doing poorly, but because there was an overproduction of flour,” says Munksgaard.

The mill's closure in 2008 marked the end of 370 years of production in Kristiansand (the first establishment took place in the Grim neighbourhood in 1641). In 2010, the city council decided that the silo should be preserved.

Great opportunities for Art and Experiences

It is April 2015. The population of Norway has passed five million, and Kristiansand now has close to 90,000 inhabitants. The second chapter in the silo's history begins. Nicolai Tangen donates a magnificent and very generous gift to the Sørlandet Art Museum: His private art collection – the largest and most comprehensive private collection of Nordic art from the period 1910 to 1990.

At the same time, he proposes that the grain silo be converted into Kristiansand's new art museum. The idea is well received, and in 2016, Kristiansand city council sets aside fifty million kroner for a future art museum in the silo building. The following year, Mestres Wåge Arquitectes and MX_SI architectural studio (now Mestres Wåge Arquitectes, BAX and Mendoza Partida) win an architectural competition, standing out among entries from 101 architectural firms across seventeen countries. The jury highlights the architects' elegant balance between the building's original appearance and its inherent sculptural and spatial possibilities.

The Kunstsilo project is fully funded in the summer of 2019, and work on the silo begins in September of the same year. The project is now on track for completion, with the Kunstsilo expected to be ready for occupancy by November 2023.

“I had never envisioned the silo being repurposed; I assumed it would eventually face demolition. Hence, it is truly gratifying to see it transformed into a hub for art and culture,” says Jan Henrik Munksgaard.

“Across the world, there is a growing trend of transforming industrial buildings into spaces for art exhibitions. It is exciting to see Kristiansand join this movement. The fact that we have done this too, especially with the renowned Tangen collection and the added advantage of being near the theatre and concert hall, really sets the stage for a successful cultural hub in the region. This initiative opens vast opportunities for artistic and cultural engagement in our community.”